Protesters dressed in red outfits from the series “The Handmaid’s Tale,” based on the novel of the same name that tells the story of women’s captivity, have taken hold of the images of the casualties and wounded of the Iranian protest movement in London.

The first year of the new century can be called the year of Mahsa, the year of Nika, the year of Yalda, and the year of all Iranian women who have spent their lives in the struggle for freedom- a year that remains memorable in the history of Iran with the roar of its youth.

More than a century has passed since the women’s movement began. Many years have been named after them: 1910, the year of constitutionalist women’s newspapers; 2006, the year of women’s movements and campaigns; and 2017, the year of the girls of Enghelab Street. But until 2022, their suffering had never been so universal.

For the past decade, it had become increasingly evident that the government was tightening its grip on mandatory hijab for women; however, until September 26th, nobody knew at what speed this struggle would jeopardize the existence of the Islamic Republic; the day a hand with a marker wrote on a cardboard: “You will not die; your name will turn into a symbol.”

The American magazine Time introduced “Iranian Women” as the “Person of the Year” for 2022.

The magazine praised the protests of Iranian women, stating that their movement is a leading force in the fields of education, freedom, and secularism. The current wave of protests in Iran, which began with the presence of women in late September and is now in its twelfth week, initially took shape in protest against the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old citizen who was killed during her detention by the Basij paramilitary forces.

Iranian women protesters demand the abolition of mandatory hijab and chant the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom.” Time magazine states that what is happening in Iran now is different from the past. The magazine says, “Today, the demands of all those seeking change are being displayed, and they are embodied in the chants of ‘Woman, Life, Freedom.'”

According to reports, the number of women appearing on the streets of Iran without the mandatory hijab has significantly increased during this period. The officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran have shown resistance to the demands of protesting citizens, and Mohammad Jafar Montazeri, the Attorney General of the country, has stated that the judicial system will continue to react to women’s attire.

While government officials, including 83-year-old Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, do not officially recognize the protests and refer to them as “sedition,” the brutal and widespread suppression of the protesters by armed forces continues.

“The Women’s Revolution”

On September 27, 2017, Vida Movahed stood on a platform at the intersection of Vesal Street and Enghelab Street, giving rise to the Girls of Enghelab Street movement.

During that summer in Tehran, when the heat had no escape from under the long coats, two months before Mahsa (Jina) Amini was arrested and her lifeless body was handed over to her family, a woman wearing a chador got into an overcrowded bus and got into a confrontation with a writer and artist named Sepideh Rashnu. During this confrontation, the woman with the chador injured the writer’s hand. With the help of other women, they forced the chador-wearing woman to leave the bus. However, security forces were able to identify and arrest Sepideh Rashnu.

After missing for several days, she appeared in a forced confession video, with a bruised face and a desperate,broken voice. Soon, the anger that was absent from Sepideh Rashnu’s tired face erupted from tweets and social media comments; a woman who had been “wronged” in the public eye and in front of cameras was arrested and forced to make a coerced confession.

For the public, Mrs. Rashnu and what she went through were part of a process that had started years ago and was becoming harsher and more complicated day by day. In the Islamic Republic, alongside the continuous efforts of women to change the strict hijab rule, the government was also tirelessly trying to prevent the retreat of women’s headscarves.

The ongoing struggle between the religious government of Iran and women for the enforcement of compulsory hijab has experienced an unprecedented turning point since 2017. In December 2017, Vida Movahed stood on the platform in Enghelab Street and waved her headscarf on a stick, a symbolic act resulting from accumulated anger that other women continued, many of whom were subsequently detained.

Sociologists had warned about the culminating point of this “public anger.” One of them, Mehrdad Darvishpour, wrote in an article in the same year: “Although these actions have not yet become widespread, their reflection and the alarming reactions of the authorities indicate that the Islamic Republic has realized that four decades of efforts to enforce hijab through imposition have not only been unsuccessful but also fears that the growth of this phenomenon could lead to a feminist revolution that could become a threat to the system.”

Why the hijab?

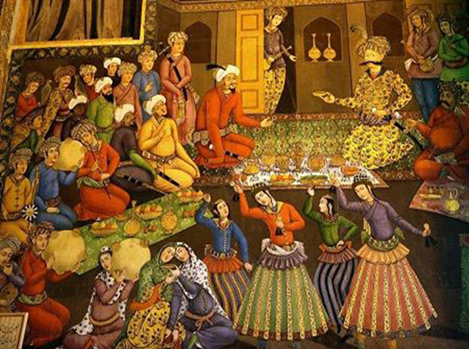

A photo of working women protesting in public administration offices, shaking their headscarves in protest against attempts to enforce hijab in the offices (Photo by Kaveh Kazemi, 2002)

In February 1979, thousands of women took to the streets in protest against compulsory hijab, but their voices were not heard. From that march in February 1979 until the time when compulsory hijab was gradually implemented in public administration offices as the “demand of the clerics of Qom” and eventually became a law within five years, many women repeatedly demonstrated their resistance to it.

However, the issue of women and compulsory hijab went under the shadow of bloody political conflicts in the early years of the establishment of the Islamic Republic, in which an unprecedented level of violence began. While the military attack by Iraq soon influenced all the political and social transformations in Iran, and in a situation where, in addition to the danger of occupation, the process of arrests and executions of political opponents continued intensively, Islamists succeeded in making hijab compulsory in addition to gaining complete control over power.

From that time until more than three decades later, when the Islamic Republic stabilized and compulsory hijab became a natural and everyday part of Iranian society, resistance to compulsory hijab was not a widespread concern. This was happening while, for some women, compulsory hijab was a visible and blatant symbol of widespread discrimination that, in their view, was implemented in a derogatory manner.

After the end of the war and in the early 1990s, Iranian society still avoided street protests due to the memory of suppression and executions in the first decade of the “Islamic Republic” establishment. But during that period, when the level of political turmoil did not have a significant difference compared to previous years, in February 1994, a woman committed self-immolation in an unprecedented act of protest without hijab.

When Homa Darabi self-immolated in Tajrish Square with gasoline, for years, no one knew that she was one of the best child psychiatrists in Iran who had lost her license to practice medicine and her teaching position at university, because she refused to comply with compulsory hijab; she was an active political woman who was aware of the “authority” of the government over her body.

Compulsory hijab was enforced with significant strictness in the first two decades of the establishment of the Islamic Republic.

Compulsory hijab was one of the ideological foundations of the Islamic Republic to control women, who were supposed to claim their share of social, political, and economic equality in the near future. The slogan “either a headscarf or you will be beaten on the head” was the starting point of a policy that first aimed to impose hijab and then reduce women’s role to obedient mothers and wives through gender segregation and discrimination.

It was not without reason that, alongside other civil movements, activists who taught women how to defend their rights during divorce were gradually arrested one by one.

However, the struggle of women against discrimination, which had regained momentum in the third decade of the Islamists’ power, with young faces and fresh ideas, entered a new phase during the fourth decade of the Islamic Republic’s establishment and expanded alongside the deepening rift between a group of citizens and the ruling power.

On the other hand, the leaders of the Islamic Republic quickly demonstrated that they are not willing to retreat as much as they are not willing to compromise on the issue of hijab and women, just as they are not willing to accept democratic changes and the political participation of citizens, to the extent that after the protests of the “Girls of Enghelab Street” in 2017, Ali Khamenei considered this act, like other protests of that year, a conspiracy by the “enemy” to overthrow the Islamic Republic. The Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran had defined the most important role of women in his speeches: “The manager and the axis of the family, mother, wife, and source of tranquility in the family.”

However, the political and social developments in Iran did not proceed according to the wishes of the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, and women expanded their disobedience more than ever before and ultimately demanded a “free society.”

And the historical turning point of this long-term struggle was also the funeral ceremony of Mahsa (Zhina) Amini in Sanandaj, where the mourners chanted the slogan “Zhen, Zhian, Azadi” (Women, Life, Freedom), and this slogan was quickly heard in every corner of Iran; a slogan derived from the political theories of Abdullah Ocalan, a Kurdish activist who has emphasized in the past two decades within the framework of the “ideology of liberated women” that the way to liberate the Middle East is women’s freedom and believes that this issue should be one of the highest priorities for those fighting against despotism in this region.

“You, whose love is life.”

On the day when the images of Mahsa Amini in the custody of the Guidance Patrol were published on Tehran’s Vozara street, many were surprised why she was arrested while wearing a loose and long coat with a scarf on her head.

The government insisted that she had an illness, and that nothing had happened to her in the Guidance Patrol’s custody. But what had the cameras inside the Guidance Patrol’s car recorded that was never released?

Some wrote on social networks, “Mahsa could have been my daughter,” “Mahsa could have been any girl walking down the street.”

Mahsa Amini’s death was a wake-up call to a predominantly young Iranian society that saw themselves in her —women who must deny themselves in order to survive. To preserve their jobs, not to be expelled, to get a passport, and even to buy yogurt from the neighborhood grocery store, on the wall of which it is written, “We apologize for denying services to not properly veiled women.” Women whose worth has been reduced to a piece of fabric on their heads.

Azar Nafisi, a writer, and former professor at Johns Hopkins University in the United States, says, “The arrival of the Islamic Republic, took away the historical, cultural, and social identities of individuals, and the work that Mahsa and other women did to liberate their lives and seek freedom was an attempt to reclaim their lost identity.”

Based on this interpretation, Mahsa Amini, who had come from Kurdistan to visit Tehran, became a symbol that, although she died, her legacy became a way of life for us.

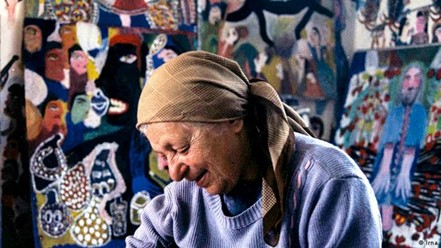

Photos of unveiled female Iranian artists

The author of the book “Reading Lolita in Tehran” says, “When they tell you that you can no longer remain the way you are and that you must be something else, it is a form of death. Mahsa only wanted to be herself. Being Mahsa meant not being part of the Islamic Republic. With Mahsa’s death, we also moved towards life, and it became evident that life is not possible in the Islamic Republic, and we must reclaim our lives.”

And ultimately, neglecting this very demand to “be Mahsa” became the biggest challenge of the 40-year-old Islamic Republic; a challenge that was met by thousands of people in hundreds of cities for consecutive months, and during which nearly 500 people, including dozens of children, were killed.

While the government tried to suppress the protests with violence, it did not refrain from resisting women and their demands. From the arrests and daily threats against “unveiled” women to various plans that receive special budgets in the parliament, public administration offices, the Revolutionary Guard, and the security forces, they have tried in every possible way to turn back the timeline of Iranian women’s struggle before 2022.

However, these days there are women walking on the streets of Iran with their hair flowing in the wind, declaring that they have chosen life, some with fearful eyes of an impending attack lurking from every direction. They come together, give each other signs of victory, and walk calmly and firmly. Some do not wear a veil on their heads. Some throw it over their shoulders. Some wear headscarves and accompany unveiled women with a smile.

Some of them, upon exiting the interrogation room, publish their unveiled photos in the very place they were arrested; women from inside the prison also shout, “I won’t return until the day I die.” And indeed, many of these women are already dead, and a bird is flying next to the number 2017 on their gravestone – a year named after Iranian women.

Yes, we have learned in this land that the path to happiness is freedom, and the path to freedom is courage.

Author: Amir Sharifi.