Art in Iran, especially the process of painting in contemporary art, has undergone significant changes and transformations based on social, political, and cultural conditions, and direct interaction with governmental ups and downs. Women, as members of this sphere, have experienced different positions, statuses, and roles in various eras.

Based on research, female painters found suitable opportunities for education after social developments from the Safavid period onward and the evolutions that took place during the Qajar era. They were able to establish themselves as independent artists in the Iranian art scene. Over time, with the emergence of civil movements and the realization of social freedoms, the role of female painters became more prominent, to the extent that today female painters have a prominent and important position in contemporary art in Iran.

Throughout Iranian history, we observe various depictions of women in different periods, influenced by political, social, and cultural considerations. We easily realize that there are very few references to female artists and painters. We have only heard that Iranian women have been artists, but only in one or two limited artistic disciplines without mentioning their names and identities, at least until the 20th century and the formation of women’s liberation movements.

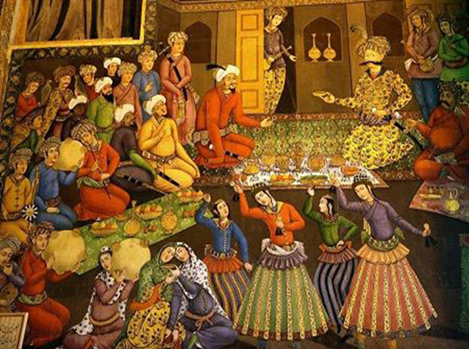

It seems to have been a principle in the past to depict women on the sidelines and in the shadow of men. In most cases, women have had limited participation outside of household matters, and their presence in painting was solely as models, used to capture their facial beauty for embellishing palaces and noble houses.

Art in Iran has always been influenced by male dominance and patriarchy. Historic documents describing the painters’ circumstances in the past reveal this discrimination. However, with the passage of time, after the Safavid era and the emergence of limited social freedoms, the art phenomenon gradually moved away from the control of the court, and in the Qajar era, this process underwent a transformation.

Since various political, economic, and cultural factors influence social roles, the position of female painters and their presence in Iranian art are always evolving.

Certainly, the recognition of women’s art, especially their historical position in the Iranian art scene, is limited, and there is room for further study.

Women in the history of Iranian painting:

After a short time following the advent of Islam in Iran, the rights that women had at the beginning of Islam were gradually taken away from them, and men gained absolute power. This male-dominated trend, especially during the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, became pervasive, similar to a cultural legacy transferred from certain conquered territories to the conquerors.

In addition to ignoring women’s rights, Islam, which considered figurative art undesirable, did not leave room for discussing women as artists during its early centuries. In the Seljuk period and afterward, when painting and art found their place, it might be possible to talk about women, but they were only subjects in artistic works. Although, it is impossible to find the name of a female artist in the history of art in the 7th and 8th centuries, we will explore the position of women during the Mongol, Timurid, and Safavid periods, as they had a special place in Iranian literature and painting.

With the arrival of the Mongols in Iran, the gap between theoretical Islamic laws and their implementation widened, and women became more confined to their homes. However, women made efforts through various means to leave their homes and participate in public gatherings. During the Mongol and Timurid periods, due to the unsettled and unstable political and social conditions in the country, women were practically prohibited from entering society. Unfavorable conditions hindered their education. In such circumstances, only a few elites hired teachers to educate their daughters at home.

Although the position of women in Iranian literature is commendable, their social realization may not have been so. Nevertheless, the rich literary and mystical influences have been effective in painting images of women as celestial lovers, but the social context has been a stronghold of male dominance, limiting the presence of women.

However, during the Safavid era, after some transformations took place, women gained more freedom of action. They not only appeared as exclusive subjects on canvases but also had the opportunity to learn and practice art and painting under the guidance of masters. Despite all the social problems and the patriarchal system in Iranian painting, one can find evidence of a few female painters, such as Azar, who was famous for her lacquer and pen-case painting during the late Afsharid period.

“Roghayeh Banu” was one of the Muslim female artists in the court of the Mughal rulers in India and was a miniaturist. She left behind a notable body of work. “Sahifeh Banu” is considered one of the most prominent female miniature painters of the tenth century among the female artists of India. She was one of the disciples of Kamal al-Din Behzad. She demonstrated skillful handwork in depicting various characters, powerful brushwork, and delicate portrayals of landscapes and faces.

Aminah, an 11th-century artist, was a painter and a follower of the Reza Abbasi school. Two of her miniatures have survived.

The Active Presence of Women in the Constitutional Era

The active presence of women in the Constitutional era and beyond in society led them to organize themselves and form various associations. “Anjoman-e Azadi-ye Huriyat-e Zan” (Association for Women’s Freedom) was the first women’s organization that emerged around 1938, with the presence of two daughters of Naser al-Din Shah, Shams al-Muluk Javaher and Seddiq Dolatabadi.

After the Constitutional era and the increase in the number of girls’ schools, the idea of unveiling gradually grew among educated women, as these schools were either run by religious missionaries or graduates of missionary schools or managed by foreigners. Among the intellectuals, there were men who believed that the veil hindered women’s progress and actively campaigned for its removal. Iraj Mirza Shahzadeh Ghajar was one of the pioneers who opposed the veil and supported its abolition and freedom of expression.

These extensive social and political transformations were manifested in the efforts of female and male intellectuals to validate women’s activities in the field of art. During the Qajar period, with the increase in the number of girls’ schools and more freedom in education and upbringing for women, the number of female artists and painters rose. Among them, we can mention Taj al-Sultan and Turan Fakhr al-Dawlah, daughters of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar. Taj ol-Soltan, Turan Fakhr al-Dowleh, and Forugh ol-Moluk were female painters.

Turan Fakhr al-Dowleh Taj ol-Soltan

Forugh al-Moluk, born in 1957, was a skilled painter in watercolor and miniatures. She was the daughter of Mirza Ali Khan Zahir al-Dowleh and had expertise in watercolor painting and artistic techniques. She painted a watercolor image of her brother, which resembled the works of Sani al-Molk, and it was sold at Christie’s auction in London in 1989.

Shokat al-Moluk Shaqaghi was an artist in painting who learned painting under the supervision of Mirza Ali Khan and Kamal al-Molk. She produced hundreds of paintings of landscapes and various portraits, and for a while, she taught painting at the Women’s Art School, mainly working in the classical style.

Efat al-Muluk Khajeh Nouri, the sister of Shokat al-Moluk, was an artist who was honored for her numerous services in art and the establishment of Tehran Girls’ School. The school was named Khajeh Nouri Girls’ School in her honor. She became a member of the Women’s National Association in 1921 and later participated in the activities of the Women’s Party, known as the Women’s Council.

Efat al-Moluk Khajeh Nouri and Shokat al-Moluk

However, the social progress of women in the field of art reached its peak with the return of open-minded students from Europe.

Pahlavi Period and Female Artists

The Pahlavi period is the era in which revolutionary poets and writers like Eshqi, Aref Ghazvini, and others entered the field of political and literary activities, and political literature flourished. This period witnessed the activities of women such as Parvin Etesami, Simin Behbahani, and Forough Farrokhzad in the field of poetry, Simin Daneshvar in the field of writing, and numerous singers and musicians. It also saw the participation of many women in various artistic fields, such as calligraphy, painting, and other artistic fields.

Women, due to their activities for the revival of their rights since the Constitutional Revolution, saw illiteracy and their own counterparts as obstacles to achieving their goals. Among them, some women made efforts to establish schools, while others who were educated worked even without rights or wages. After the departure of Reza Shah and the formation of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s government, social freedoms increased with a demand for renewal. The exposure of the country to various beliefs and ideologies, mostly imported, created a diverse artistic environment for both male and female artists.

Iran Darroudi

The Faculty of Fine Arts at this time was a center for the manifestation of modernity in scientific and cultural forms. In the transition from traditional forms to renewal, efforts that had begun with Abbas Mirza and Amir Kabir and took shape during the Constitutional period were now being realized. The acceptance and presence of women as teachers and students were important factors in the extensive social presence of women in the arts.

An interesting point to note in this period of contemporary art and culture is the presence of female painters from the very beginning of the introduction of modernity into various social spheres. For example, in the field of painting, we encounter the names of female artists such as Leyli Taghipour, Shokouh Riazi, and Fakhri Engha (although initially the number of women was small compared to men, this minority’s presence is a sign of the realization and achievement of some of the ideals of Iranian women’s liberation).

Fakhri Engha Shokouh Riazi Leyli Taghipour

In this process, modernism apparently provided a path for the extensive presence of Iranian women in all cultural, social, and political aspects. The modernization process in Iranian society, despite its ups and downs, delays, and negative consequences, was a field in which Iranian women could move toward their human identity. For centuries, the dust of traditional and extremist beliefs had obscured and damaged their identity, but now they could express the unsaid and unheard with art and literature as their means.

Culture and art, especially painting, provided an appropriate platform for Iranian women to unveil their faces, step out of the confines of their homes, and express unspoken and unheard words. This was due to its inherent nature and potential, as well as its affinity for femininity.

After the 1979 Revolution and the Contemporary Period

After the 1979 Revolution, the resignation of the interim government, and the dismissal of Banisadr in June 1981, the dominant discourse became Islamic-oriented, which continues to this day. However, the grand discourse of Islamic orientation has undergone transformations and fluctuations over the past four decades. The result of this internal transformation has been the emergence of five minor discourses.

These minor discourses are: ummah-oriented idealism, center-oriented pragmatism, development-oriented realism, people-oriented peace, and justice-oriented principles. On the other hand, during the war period, idealistic and pragmatic discourses dominated the era of construction, while in the period of reforms, people-oriented peace discourse prevailed, and after the ninth presidential election, the discourse of justice-oriented principles became dominant over the Islamic Republic, all without beneficial or constructive effects on society.

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the lives of Iranian women have been slow and arduous. In addition to the limitations imposed on them by the conservative, male-dominated society, they have also faced increasing pressure from the social and legal systems of the Islamic Republic. This is especially true among the poor and middle classes, who live in small towns and rural areas and are generally traditional.

Throughout vast Iran, customs, religions, ethnicities, and even languages vary from region to region, but the government’s control over every aspect of women’s lives is the same everywhere.

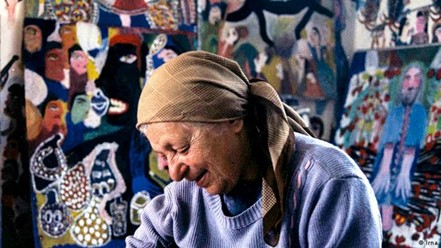

Many women in Iran strive to bring about change in their society, each in their own way. However, artists have their own platform to reform deep-rooted societal views regarding women. In fact, Iranian artists have used art as a means to bring about social transformations, express dissent, and challenge the oppressive patriarchal system imposed upon them.

Systematic Discrimination

Hura Mirshakari, an artist and visual performer, echoed many of the points Nasrat had raised, saying: “The restrictions imposed on Iranian women begin with the family. Families adopt these restrictions from society, traditions, and religious beliefs. These limitations prevent women from choosing their partners, wearing the clothes they desire, styling their hair as they wish, depicting their desired subjects, and so on.

Tarlan Lutfizadeh, an artist, said: “The entire system is based on male dominance and regulations, some of which have Islamic roots and others that do not. These regulations are mainly built on the belief that men are complete beings capable of thinking and making decisions for themselves, while women are considered semi-human and devoid of such abilities.”

Protest through Art

Aida Nosrat, an artist, believes that being true to oneself is the best way to fight against the Iranian regime: “By delving into my own depths and finding the real Aida buried beneath the impurities that have plagued me since childhood, I can live with dignity and succeed in my art and music. This is the best way to fight against such individuals, as they ultimately belong to shadows and darkness, not to the truth.”

Mirshakari’s range of works includes expressive performances, singing, painting, and sculpting. Her focus is on women, the female body, and the obstacles imposed on women’s lives: “The main themes of my artworks usually revolve around women and the limitations they face. For example, my recent project is about singing in my own native language [Sistani]. We don’t have any female singers from our region, and it’s like a taboo. I hope this project opens the way for women’s singing in my city.”

Hura Mirshakari

Tarlan Lutfizadeh, also an artist, channels her art in the same direction. She told Emrooz Media: “I do whatever I can to increase women’s awareness of their rights and make men reconsider their actions in light of all these laws and powers they enforce against women using the country’s legal system.” She concluded her statement by saying, “I strive to question, freely express my beliefs, and fight against traditional beliefs. I do this as an artist, as a feminist, and as someone who cannot stand by in the face of this discrimination against women.”

Author: Amir Sharifi